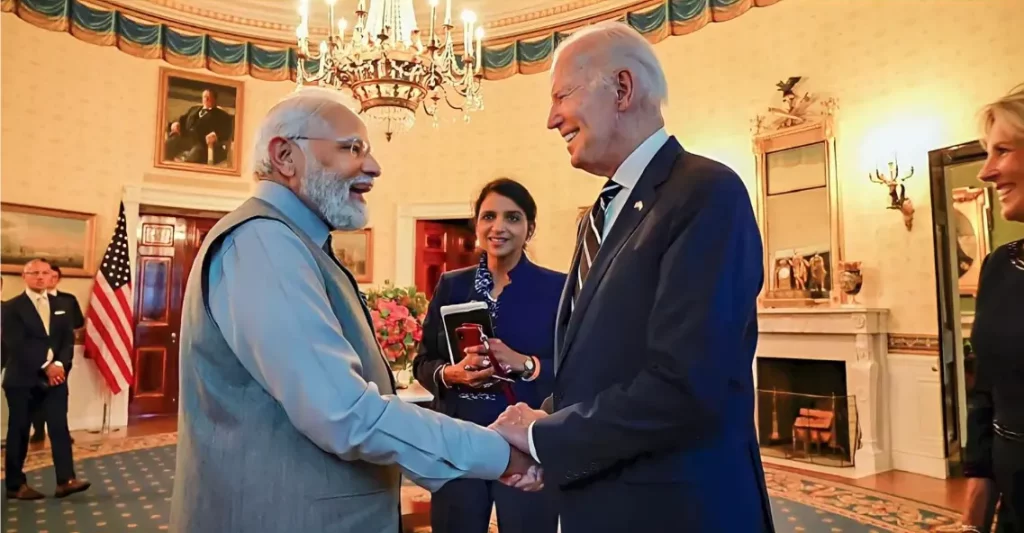

(February 20, 2026) Right from the presidential years of Barack Obama to Joe Biden and now Donald Trump, in bilateral talks with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Gurdeep Kaur Chawla has been present in those high-stakes meetings, headset on and mind alert, carrying the conversation from English to Hindi at the highest level of power.

And it has not been limited to American presidents. She has worked closely with Canadian prime ministers Stephen Harper, Justin Trudeau and most recently Mark Carney, accompanying delegations, travelling on official visits, and interpreting during bilateral meetings where diplomacy is measured word by word. From Washington to Ottawa, from New Delhi to global summits, her voice has travelled through some of the most consequential rooms in contemporary geopolitics.

“When you’re sitting there, you’re not just translating. You are in the moment listening, analysing, predicting the next sentence. You have to understand the chain of thought. You have to also understand what is behind the words,” Gurdeep says in an interview with Global Indian.

It was this ability to become the alter ego of the speaker that once moved the late Sushma Swaraj to introduce Gurdeep to dignitaries with pride, saying, “Yeh to meri awaaz hai.” She is my voice. For Gurdeep, it was the highest professional validation from the then external affairs minister of India.

Modi at the UN, her voice to the world

In 2014, when Narendra Modi delivered his first address at the United Nations General Assembly, the camera was fixed firmly on him. But the global broadcast carried Gurdeep’s English interpretation. World leaders, diplomats and international media heard her voice rendering his Hindi into English in real time. She had slept barely two hours the night before due to long red-eye flight coast to coast and was live at the UN by 9 AM. That interpretation now sits permanently in the UN archives.

At G20 gatherings, including recent summits where Modi addressed assembled heads of state, Gurdeep’s words travelled through headsets across vast conference halls. Presidents, prime ministers and senior diplomats were receiving her voice as the bridge between intent and understanding. It is a rare space to occupy, unseen yet central, where meaning must land exactly as intended.

Not just words, it is responsibility

Gurdeep is careful about what she says publicly. “Since I work with the highest offices, whatever happens in the meeting room stays there.” Confidentiality, for her, is not a clause in a contract. It is the backbone of the profession. She will never recount what one leader said to another. But she is clear about what it takes to stand between them.

At a diplomatic level, interpretation is never literal. It is layered with nuance, political sensitivity, cultural context and emotional tone. “The interpreter has to get under the skin of the speaker,” she explains.

That means preparation that borders on obsession. Before interpreting Modi during his early global appearances, she spent weeks studying every speech she could access. She listened to his diction, observed his cadence, analysed how he structured arguments and how he built emotional emphasis. “It’s not like you just go and say, okay, I’ll interpret,” she says. “You have to know how the next sentence might come.”

Simultaneous interpretation leaves no room for delay. Hindi often completes meaning at the end of a sentence, while English demands structure earlier. “You don’t have the luxury to wait. If you keep waiting, the speaker has gone ahead and you lose something crucial,” she says adding, “The person listening should get the impression that they are listening to the original speaker, not to Gurdeep Kaur Chawla.” That requires mastering the register. Between two heads of state, the tone must remain precise and diplomatic. At a town hall, it must soften and connect. “We wear many hats,” she says. “You have to know your audience.”

Cultural sensitivity is constant. “Suppose a speaker quotes Shakespeare to an audience unfamiliar with the reference, an interpreter must instantly find an equivalent that carries equal impact. Maybe bring something from the Mahabharata or Ramayana,” she says. “It has to strike with the same amount of force.” In her words, interpreters are ambassadors of culture as much as language. They must be walking encyclopedias, constantly updating themselves on global affairs, new terminology, evolving acronyms and policy shifts. “If I go unprepared,” she says, “I will make blunders at a very big level. And that cannot happen.”

Beyond politics, into global boardrooms

Although most visible in political settings, Gurdeep’s professional footprint extends into corporate and global business arenas. She has interpreted at major multinational conferences and for Fortune 500 companies including Pfizer, Merck and Pepsi.

Through such assignments she came to work closely with Indra Nooyi, someone she once admired deeply. “She was a role model,” Gurdeep recalls. “I used to listen to each and every speech of hers.” Years later, she was interpreting for her at conferences and annual meetings. The shift from attentive listener to trusted voice carrier reflects the arc of her career.

Building an institution

Gurdeep is also the Founder and Director of Indian Languages Services, headquartered in California with offices in Canada, Mexico and India. The agency provides high-level interpretation for political, corporate and pharmaceutical engagements. Her interpreters are carefully selected professionals, many affiliated with global associations such as the American Translators Association and other top-tier bodies.

“We don’t compromise,” she says. “At G20, G7, climate conferences, even slight misinformation can cause huge loss.” Precision is not optional. It is protection.

Trained on the floor of Indian Parliament

The discipline that defines Gurdeep Kaur Chawla today was forged in the Indian Parliament in the early 1990s. Armed with a Master’s degree in English Literature from St. Stephen’s College, Delhi University, Gurdeep had not initially imagined a career in interpretation. But once selected as a trainee interpreter in the Lok Sabha, she entered a training system she still describes as unparalleled.

For close to two years, she trained under veteran parliamentary interpreters with decades of experience. She began by observing from the booth. Then came five minutes of live interpretation. Then ten. Then fifteen. “They were watching me like a hawk,” she recalls.

Every few months there were formal tests. Senior interpreters would read passages while she interpreted in real time. They recorded her voice, replayed it and dissected every sentence. “Why did you use this word? Why not that expression?” It was intense and exacting. “I don’t think a university can replicate that kind of training,” she says. “Four senior interpreters sitting with you, analysing every word.”

She was trained in both directions, from Hindi to English and English to Hindi. Initially she resisted, believing her English was stronger. Later she realised how crucial that decision was. “It was a blessing in disguise,” she admits.

Starting again in America

In 1996, Gurdeep moved to the United States due to her husband’s work commitments, believing it would be temporary. She took leave from Parliament, expecting to return in three years. In the US she could not imagine staying idle.

Living in Silicon Valley, she briefly considered technical writing or IT courses. Her husband offered simple advice. “If you’re not happy, you won’t succeed. Follow what you’re good at.”

So she printed her resume and walked into local courthouses in California. These were the mid-1990s, long before professional networking platforms. Within weeks she began receiving assignments. She cleared local court certifications, then federal exams. A colleague later suggested she attempt freelance diplomatic interpretation in Washington, D.C. Gurdeep hesitated, then tested, then steadily cleared levels over time.

In 2010 came the breakthrough. She was asked to accompany President Barack Obama on his visit to India to meet Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Returning to Parliament, the very space where she had once trained, now as part of a U.S. presidential delegation, felt surreal. “Life was coming full circle,” she says. After that, her career expanded rapidly across administrations and continents.

The power of the human voice in an AI age

Gurdeep’s reflections on artificial intelligence come from experience, not apprehension. “Once you say a word, it cannot be changed,” she says. “It’s like the arrow that has been shot.” An interpretation delivered at the United Nations or in a bilateral meeting becomes part of a permanent record.

She acknowledges that AI is a powerful tool for documentation and preparation, especially in an era of remote platforms and large language models. But she draws a clear line where, in her words, “the soul of communication begins.” She calls it the Empathy Barrier — the point where data ends and human connection begins.

AI can process probability and syntax. Diplomacy, she argues, happens in subtext. “You feel the pulse only when you’re sitting there,” she says. “You see body language. You understand the tone.” A literal translation of sarcasm, pause or idiom can shift meaning in sensitive negotiations. A seasoned interpreter translates intent, not just words.

“In a closed-door meeting, leaders don’t look at a screen for reassurance,” she says. “They look at the human being in the booth.” Beyond the Empathy Barrier, she believes, trust still belongs to people.

The interpreter’s paradox

For more than three decades, Gurdeep Kaur Chawla has stood in rooms where policy is shaped and history is spoken before it is written. She has interpreted for prime ministers and presidents, corporate leaders and global institutions, at G20 summits and UN assemblies. Yet the measure of her success lies in invisibility.

“If the interpreter disappears,” she says, “and the audience feels they are listening to the original speaker, that is the true test.”

In a profession where a single word can tilt meaning and a misplaced emphasis can alter tone, her responsibility is not to be remembered. It is to ensure that what was meant survives the journey across language. Perhaps that is why Sushma Swaraj’s introduction still resonates. To be someone’s voice, accurately and without distortion, is not performance. It is trust.

Throughout it all, Gurdeep has carried her mother’s advice with her. “It’s one thing to achieve success and another thing to maintain it.” For her, that has meant working harder after recognition arrived, not easing into it. “Now the world’s eyes are on you,” her mother says. “You always have to maintain that level.” In rooms where a single word can carry the weight of nations, that reminder steadies Gurdeep.

- Follow Gurdeep Kaur Chawla on LinkedIn

ALSO READ: Rooted in Legacy, Driven by Vision: Dhruva Jaishankar and Vishwa Shastra